Yucatecan Embroidery: Heritage and Maya Identity

The roots of Yucatecan embroidery trace back to the times of the ancient Maya, as evidenced by fabric remnants found in the Chichén Itzá Sacred Cenote. In Yucatán, there are textile artists (both women and men) across the state’s 106 municipalities. In Yucatán, they master at least 30 of the 40 existing embroidery stitches in the country; as such, embroidery stands as one of the most significant symbols of identity, and recently, of economic progress.

UNESCO and Maya embroidery

In 2023, the initiative “Economic and Social Development with a Gender Perspective through Textile Art in Yucatán” was launched. Its main objectives include strengthening Yucatecan textile art, dignifying those who practice it, recognizing its cultural, social, and economic importance, promoting gender equity, and developing a Safeguarding Plan that ensures its viability. UNESCO implemented this initiative with valuable contributions from the BANORTE Foundation as well as the Yucatán state departments of Culture and Arts (SEDECULTA), Women (SEMUJERES), and the Yucatecan Institute of Entrepreneurs (IYEM).

The role of embroidery in Maya life

Embroidery has been an essential part of the Maya population’s life cycle. From birth to adulthood, ceremonies such as Jéets’ Méek’, (a social initiation practice to introduce Maya children to society) are adorned with embroidery.

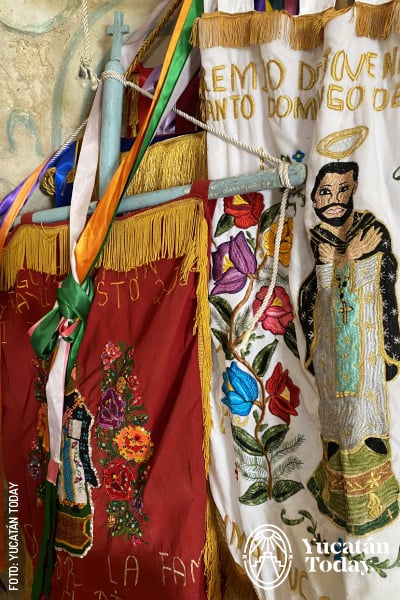

Additionally, religious and spiritual life is enriched with embroidered shrouds, gowns for religious figures, banners, and standards. Women wear embroidered dresses during guild festivities and Vaquerías (traditional Yucatecan celebrations) dedicated to the patron saints of towns and cities.

Maya embroidery as part of religious celebrations

Beyond its symbolic and religious significance, embroidery has given rise to beliefs and is integral to the Maya worldview. It is also closely tied to the milpa, the traditional agricultural system that provides sustenance for families and has contributed to the existence of the jungle and its biological richness.

Maya embroidery, central to Yucatán’s traditional dress

The Hipil and Fustán, which constitute Yucatán’s traditional female attire dating back to pre-colonial times, are embroidered at the neckline and hem in a distinctive design pattern. This allows for the identification of those who wear them as belonging to the Yucatecan land. But it goes beyond that—it also enables the identification of specific regions based on the type of embroidery, composition, and colors.

In essence, embroidery is both a heritage and an identity of the Yucatán Península.

A Brief History of Yucatecan Maya Embroidery

Embroidery in Yucatan has a centuries-old history. According to Graciela García Lascurain, a restorer at the Mexican National Institute for Anthropology and History (INAH), while there are scholars who argue that embroidery was introduced by the Spanish, there is archaeological evidence of the presence of embroidery (in addition to weaving) from pre-Hispanic times. She described the techniques found in textiles dredged from the Cenote of Chichén Itzá, and reported, back in 1989, seven weaving and one embroidery technique: Chuuy K’ab, known as “satin stitch”.

There is another stitch, the Xmanikté, which may be pre-Hispanic and endemic to Yucatán. It has no Spanish name, and is only distributed in villages; it is a serpentine stitch, which represents the diamonds of the skin of the rattlesnake, and supports multiple Maya beliefs. It does not appear in embroidery books. Chuuy K’ab, the Xmanikté, and Xookbil Chuuy (“counted thread” or cross stitch, introduced by the Spanish), have been, along with other stitches, pillars of Yucatecan Maya hand embroidery for centuries.

The traditional Yucatecan dress, Hipil (different from the Huipil worn in other parts of México), and the terno, its luxury version, are also of pre-Hispanic lineage. In colonial times the use of the hipil was confined to the Maya, while the terno distinguished mestizo women. In the 19th century, Maya and mestizas shared hipiles, ternos, and identity. They were all considered mestizas. Today the terno proudly identifies all social classes.

In Yucatán, clothing stopped being woven because the colonial gift of plain fabric ended the brocades woven into Maya textiles; instead, Maya women began to decorate their fabrics with embroidery in the 17th century. That is why Yucatán is the state with the most embroidery techniques in all of México (30 out of 40). Embroidery adorns garments for life-cycle rituals and religious, secular, and official celebrations, and there are designs, techniques, and colors that identify regions and towns.

In the 20th century, embroidery was enriched with the pedal machine that originated new techniques and designs, and with the motor machine, which favored commercial embroidery.

Now, the threat is digital embroidery which is replacing both hand embroidery and artisanal machine embroidery. Embroidery is a cultural heritage that has given and continues to provide the Yucatecan Maya people with part of their identity, and that is why on March 18 of this year, it was named Intangible Cultural Heritage of Yucatán. Safeguarding this artisanal skill is essential.

Hand Embroidery in Yucatán

In Yucatán, the practice of hand embroidery is centuries old and fortunately still alive and kicking. It is an essential activity currently practiced in municipalities in the south, east, and center of the state, especially; in Yucatán, hand embroidery is also a source of cultural identity, creativity, and family income. Yucatán is the Mexican state where the highest variety of embroidery stitches can be found (30 out of the 40 identified countrywide).

In Colonial Yucatan, the main tribute was plain fabrics that ended with the beautiful brocaded woven fabrics the Maya had created for generations. Since the 16th century, women learned to adorn their fabrics with hand embroidery, and they did so until the 1970s, when a slew of agricultural crises pushed families to seek alternative sources of monetary income; one such way was the sale of embroidered garments, which were previously created only for self-consumption. These embroidered garments entering the market led to the expansion of embroidery assisted by pedal and motor machines; while this technique is, in a way, artisanal (as it requires skill and dexterity from those who employ it), it is a different kind of “handcraft.” Hand embroidery was threatened. However, today it is still appreciated and its value revitalized, on the basis of its social and cultural wealth.

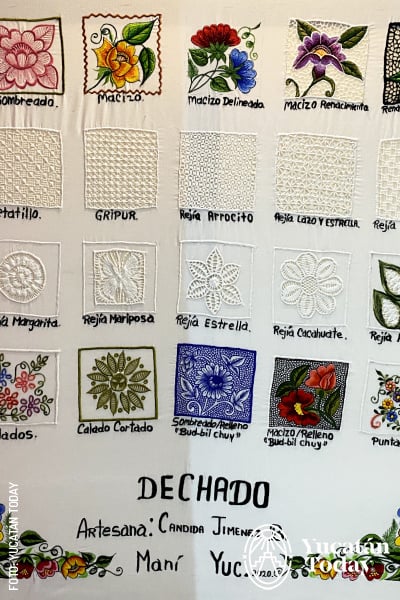

The Chuuy K’ab or “hand embroidery”, the Xmanikté, and the cross stitch have been three pillars of Yucatecan Maya hand embroidery for centuries, along with other stitches such as the Mol Mis, or “cat’s paw”, the Le’e Subin or “Subin leaf”, the backstitch, the outline stitch, the “festoon”, the chain stitch, etc., which add up to about 20 stitches, some of them including some variants.

The Xmanikté or “everlasting flower,” which is pre-Hispanic and found only in Yucatan, is a beautiful serpentine stitch that represents the diamonds on the skin of the rattlesnake, and is the support of multiple Mayan beliefs. For example, one that lives on to this day is that touching a snake’s skin will allow people to embroider quickly and well. Currently, this and other stitches are being valued and rescued.

The cross stitch arrived with the Spanish women and was appreciated by the Maya, as it was able to recreate the predominant geometric figures of ancient Yucatán associated with the snake. The Maya gave the cross stitch the name of Xookbil Chuuy, which literally means “counted thread;” in Yucatecan Spanish, it’s been known as “counted thread” since then.

Yucatecan Maya embroidery is being revitalized thanks to an ambitious project that UNESCO and the government of Yucatan are carrying out, where embroidery is being recognized as Cultural Heritage. Through this project, hand in hand with the embroiderers, a roadmap and a safeguard plan are outlined to recognize the Maya embroidery’s glorious past, to value the importance of its present, and to promote future actions.

Artisan Machine Embroidery in Yucatán

Sewing machines arrived in Mérida at the end of the 19th century, but it wasn’t until 1914 that Mrs. Esther Díaz Aguilar and her sisters spread their use for embroidery at the famous Díaz Aguilar Academy. In three years, they trained 900 people who, in turn, taught it in Mérida and in the interior, in Campeche, Tabasco, Veracruz, and other parts of México, in addition to holding exhibitions.

Sewing machines arrived in Mérida at the end of the 19th century, but it wasn’t until 1914 that Mrs. Esther Díaz Aguilar and her sisters spread their use for embroidery at the famous Díaz Aguilar Academy. In three years, they trained 900 people who, in turn, taught it in Mérida and in the interior, in Campeche, Tabasco, Veracruz, and other parts of México, in addition to holding exhibitions.

Machine embroidery made the work easier and increased the creativity of Maya embroiderers. Since the 60s, they have been given machines through credits or subsidies, as well as courses to learn new techniques. As commercial embroidery production increased, electric machines also expanded to allow greater speed, but since freeform techniques are done on pedal machines, many embroiderers use both.

The women who began using machine embroidery were the ones who were versed in Chuuy K'ab or "hand embroidery." Entering the world of machine embroidery was easier for them than for those who did cross stitch because the design, drawings, and technique on the fabric are similar; in cross stitch, the process of transferring the drawings to the fabric is very different.

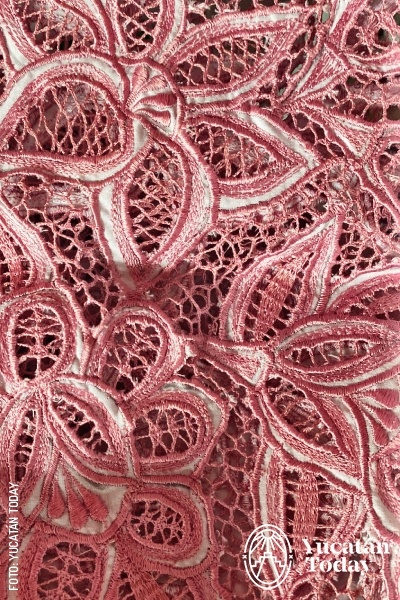

Currently, there are about 10 artisanal machine embroidery techniques. Among them, Macizos (solid embroidery styles), which present at least 5 variants, predominate. The “Matizado” styles that adorn many suits, luxury costumes from dairy farms, and traditional festivals, stand out. Openwork embroidery involves cutting fabric and constructing the embroidery in those open spaces. Latticework (Rejillas) stands out, with multiple variants that result in authentic machine-made lace. They are made on frayed fabric or on threads that are stretched like cobwebs in cut spaces, in which the drawing is embroidered and formed. Other styles include Renacimientos, Calados, and Cortados, among others.

In the 90s, digital embroidery entered Yucatán, and today it’s increasingly threatening the existence of artisanal machine embroidery and hand embroidery.

UNESCO, Fundación Banorte, and the Yucatán state government are collaborating with embroiderers from different towns and communities to develop a roadmap and preservation plan for Yucatecan embroidery. This initiative aims to ensure its continuity and pass it down to future generations.

Embroidery and Life Cycle in the Yucatán Maya

For the Maya, embroidery is not only an adornment of objects and clothing. Embroidery has accompanied Maya women and men from their birth to their death, playing a symbolic role full of cultural meaning.

Embroidery in the life of Maya men

Although men do not wear embroidered garments after the traditional embroidered diaper that wraps them during their birth, early childhood and baptism, or the handkerchiefs that their wives and daughters embroider for them—or that they embroider themselves, if they are Jaraneros (tradidional dancers)—, embroidery is permanently present in the feminine cultural landscape, daily and ceremonial, that surrounds their lives. In the past, during their early childhood, men also wore Hipilitos (a small version of the traditional garments worn by women), embroidered with animal motifs. That custom has changed lately.

Embroidery in the life of Maya women

As for women, embroidery accompanies them, in the form of clothing, throughout their lives. At birth and baptism they are covered with embroidered diapers and Hipilitos. As they age, first Hipilitos and then Hipiles or embroidered blouses and dresses protect them daily until their death. During religious festivals they dress up in embroidered Ternos, which are luxury Hipiles.

The Fustán or Justán, which is the embroidered white slip worn by the Maya, has not been part of the girl's attire, since wearing a Fustán has long been perceived as a sign of being a grown woman.

Embroidery as part of the Maya life cycle

White embroidery covers the Maya at the moments when they change state during the life cycle: at the baptism, white diapers, at the first communion, their first white Terno, and at their wedding, their second white Terno. In ancient times, golden or silver wedding anniversaries were not celebrated, because they weren’t a Maya custom. But today they are celebrated. For silver and gold wedding anniversaries, luxury Ternos are worn, and guests are even asked to also wear Ternos and embroidered Guayaberas. These are called “regional” weddings or celebrations.

Maya women are buried in Hipiles, and the dead of both sexes receive their food offerings wrapped in embroidered napkins at each anniversary of their death (when a Novena is organized for them), but also during Janal Pixan, the collective annual ceremony held to receive the souls of the dead. Mourning has been expressed by wearing Hipiles embroidered in a single color, especially black or purple.

Ceremonial and Ritual Embroidery in the Maya Communities of Yucatán

Embroidery is deeply woven into the spiritual life of Maya communities in Yucatán. A myriad of embroideries adorn popular, ceremonial, and ritual settings with a multitude of colorful floral threads.

Patron saint festivals—the annual celebrations for Catholic saints in each town—usually begin with a lively traditional dance called Vaquería. These events are filled with beautiful embroidery, decorating the Ternos (luxurious traditional costumes) worn by women. Embroideries also adorn the banners and pavilions carried by Gremios (guilds), as well as the handkerchiefs worn by Jaraneras and especially by male Jarana dancers. It is customary for the latter to embroider large handkerchiefs with xookbil chuuy, or "counted thread," as cross-stitch is known in the Maya and regional Spanish languages. Embroidery also decorates altar linens in churches and homes, the Ternos that adorn virgins and saints, and the napkins and tablecloths used for food offerings.

For the Holy Cross festivities on May 3—which hold special meaning for the Maya because of the Cross's connection to the Ceiba tree—the crosses are dressed in beautiful embroidered shrouds adorned with such colorful flowers that they look like Hipiles.

For Janal Pixan, or “food of the souls,” held in November, tablecloths for domestic altars where offerings for the souls of the deceased are placed, and napkins for wrapping tortillas, tamales, and food are embroidered. This is a way to honor and respect the spirit of the deceased, who visit this world each year.

The Jéets’ Méek’ is a special ceremony among the Maya from the Península to welcome children into society, expand their knowledge, and carry them on an adult’s hips for the first time. During this ceremony, girls often receive a needle with thread or are encouraged to touch a sewing machine to develop their embroidery skills. Boys, on the other hand, touch machetes and Coas (a gardening and farming tool) so they can learn to work in the milpa. While these traditional tools are being replaced by pencils, notebooks, and even computers or tablets, women are still encouraged to work with needles, threads, fabrics, and quality embroidery.

Spirituality, ceremonies, and rituals, so present in the everyday life of the Maya, are always accompanied by embroidery, reflecting its significance in their beliefs and Península identity. That’s why Maya embroidery is now recognized as a cultural treasure in Yucatán, with plans in place to keep this amazing tradition alive for the future.

Embroidery and Janal Pixan

In Yucatán’s Maya communities, the celebration of the dead takes place from October 31 to November 30. Although the deceased only stay in their former homes for a week, they remain close to their relatives in their villages for the entire month and say goodbye on the last day of the month.

In Yucatán’s Maya communities, the celebration of the dead takes place from October 31 to November 30. Although the deceased only stay in their former homes for a week, they remain close to their relatives in their villages for the entire month and say goodbye on the last day of the month.

While they are home, they are celebrated by the living by setting up altars with the food and drink their loved ones used to like.

The altars are covered with embroidered tablecloths and the food is placed on or covered with napkins, also embroidered.

Embroidery is a way of showing respect and pleasure for the visit of the deceased who come to the homes of their relatives once a year.

For the altars of adults, to whom offerings are made on November 1, tablecloths are embroidered with colorful flowers and green crosses.

Sometimes, elements that recall the activity of the dead are embroidered on the tablecloths; for example, if the deceased hunted, a shotgun and a deer are embroidered.

Napkins are used to cover the calabashes where tortillas are placed, and also arranged on the altar as a setting for the the fruits or sweets that are offered. These napkins are embroidered with colorful flowers and are decorated on the edges with fringes or with embroidered trims of many colors.

In Pomuch, Campeche, there is a custom of removing the remains of the deceased, cleaning them and putting them back in niches that are built in the pantheon. The remains are wrapped in cloths featuring different types of embroidery according to the deceased’s sex and age. Women’s shrouds are embroidered with flowers; men’s, with crosses; and children’s with flowers and angels. All of these celebrations, despite involving entire communities, are intimate for families and households; therefore, they must be approached with respect and without expecting anything more than what people want to share.

Embroidery plays a fundamental role in Janal Pixan and enriches the Day of the Dead celebrations. Yucatecan Maya Embroidery is part of the heritage of the state of Yucatán, and its bearers, communities, municipalities, the state and UNESCO are working together towards its safeguard.

Magical Villages and Maya Yucatec Embroidery

In Yucatán, seven municipal capitals have earned the prestigious recognition of being Pueblos Mágicos, or "Magical Towns": these are Izamal, Valladolid, Maní, Sisal, Espita, Motul, and Tekax. Each has its own unique charm, and they are all worth a visit. Take, for example, Maní, a town that offers much to its visitors but also holds a special kind of magic, hidden from outsiders yet well-known to locals.

Maní’s most famous landmark is its ancient convent, with its vast atrium that witnessed the infamous Auto de Fe of Maní. This event, led by Fray Diego de Landa in 1562, involved the destruction of thousands of sacred images, religious objects, and invaluable Maya codices. But Maní is also renowned for being the seat of the Xiu, a noble Maya lineage whose protector deity, Kukulkán, did not vanish but instead merged with the figure of San Miguel Arcángel (Saint Michael), Maní’s patron saint. Additionally, for the past 33 years, Maní has been home to the prestigious "U Yits Ka’an" Ecologic Agriculture School, which has educated countless farmers and inspired the creation of community-based tourism ventures like “Pachpakal - Solar Maya,” where visitors can explore diverse crops and traditional backyard animals. There’s also the remarkable "U Naajil Yuum K’iin" meliponary (stingless bee farm), dedicated to the preservation of native stingless bees. And let’s not forget the town’s renowned culinary specialty, “poc chuc,” a delectable grilled pork dish that can be savored in many of Maní’s restaurants.

Still, it’s surprising that embroidery is not more widely celebrated as one of the key features of Maní’s unique charm. The town is, after all, home to an extraordinary number of highly skilled embroiderers who have earned numerous state and national awards over the years. In Maní, machine embroidery reigns supreme, and it’s distinguished not just by its intricate designs, but especially by the technique known as rejilla—a kind of latticework embroidery that creates exquisite lace-like patterns, both beautiful and varied. This technique stems from hand-drawn threadwork, resulting in delicate and complex textile masterpieces. In Maní, rejilla embroidery has found its most talented hands, minds, and hearts, blossoming into a singular art form. Other noteworthy techniques include embroidery on tulle and organza, all of which are equally striking.

That said, hand embroidery is not to be outdone. In Tipikal, a small sub-municipality of Maní, ancient handcraft techniques like xmanikté, mol miis, and cinta chuuy are still practiced, with these stitches being applied to modern garments that are hand-finished with exceptional quality.

We wholeheartedly encourage you to make the most of your visit to Maní and visit a few of its embroidery workshops, so you can experience for yourself one of the most distinctive expressions of the town’s creativity and identity.

Embroidery plays a fundamental role in Yucatecan identity and enhances the experiences within its Pueblos Mágicos. The Yucatecan Maya embroidery tradition is recognized as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of the state, with UNESCO working alongside artisans, communities, and local governments, supported by Fundación Banorte, to safeguard this rich cultural legacy.

Regional Embroidery and Identity in Yucatán

The hipil (pronounced ee-PEEL) is a symbol of Yucatán’s identity. It has endured for hundreds of years and remains a common sight throughout the region. Though this garment has evolved over time, in recent decades, it has increasingly taken the form of a blouse, both in rural and urban areas. In this context, there are distinct regional and even community-based variations reflected in the embroidery of these garments, giving them a unique identity.

Following the decline of the henequen-producing region, more subdued embroideries emerged, often in a single color and using techniques that don’t require much thread, such as "shaded" fills or single-color embroidery of small flowers. Towns like Kimbilá (a sub-municipality of Izamal) and San José Oriente (a sub-municipality of Hoctun) stand out with specific, notable identities.

Embroidery in Kimbilá vs. Embroidery in San José Oriente

Kimbilá, with its many family-run workshops producing both traditional and modern embroidered clothing, has introduced designs like double-hemmed hipiles, dresses, and Western-style blouses embroidered with Yucatecan flowers—especially those from the henequen zone, often featuring single-color petals. In the more traditional San José Oriente, a distinctive double cross-stitch—known as xka kaap’e—is used on hipiles and blouses, resulting in large flowers, fruits, and other designs that give this community's clothing a strong and widely recognized identity.

Embroidery in eastern Yucatán

In eastern Yucatán, once known for its maize fields and home to the most traditional Maya population, ethnic aesthetics are vigorously expressed through the use of bright, bold colors and thread-heavy techniques such as the “macizo” (dense embroidery) and multicolored rejilla designs. In Xocén, a town south of Valladolid renowned for its adherence to tradition, hipiles made from pastel fabrics embroidered with machine-made macizo designs in bright, bold colors were once common, with nylon backings that matched the fabric. The latest fashion, however, features black hipiles with intricate cutwork embroidery and colorful geometric or floral rejilla patterns. The rejilla technique resembles openwork embroidery, but it is not—the designs are created using foot-pedal machines.

Embroidery in southern Yucatán

In the southern region, where deeper soils have enabled more profitable commercial agriculture, wealthier residents often wear hipiles and blouses adorned with elegant, wide machine-embroidered rejilla designs in a single color, as well as techniques like embroidery on tulle or gauze, and appliqué embroidery. Towns like Maní, Oxkutzcab, and Dzan stand out, while other communities like Teabo, Tahdziu, and Yaxhachen are distinguished by their cross-stitch embroidery.

In the southern region, where deeper soils have enabled more profitable commercial agriculture, wealthier residents often wear hipiles and blouses adorned with elegant, wide machine-embroidered rejilla designs in a single color, as well as techniques like embroidery on tulle or gauze, and appliqué embroidery. Towns like Maní, Oxkutzcab, and Dzan stand out, while other communities like Teabo, Tahdziu, and Yaxhachen are distinguished by their cross-stitch embroidery.

Due to its techniques, uses, ability to adapt to changing fashion trends, and significance as a marker of regional and local identity, Maya Yucatecan Embroidery has been declared an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Yucatán. Supported by UNESCO, local embroiderers have formulated a safeguarding plan to ensure the craft’s continued existence into the future.

Embroidery in the Patron Saint Festivities of Yucatan

Throughout Mexico—and especially in Yucatán—patron saint festivals bring together the vibrant living traditions of a community, town, or municipality. These celebrations unite entire populations in joyous harmony, as residents don traditional attire, prepare special dishes, dance the jarana in the vaquerías (the traditional dances that open the festivities), hold ceremonies and processions, and honor their rich cultural heritage with exuberance.

During these festivals, Yucatán’s iconic embroidery takes center stage. The intricate designs adorning the hipiles and ternos worn by women, the banners and flags representing religious guilds, the elaborate handkerchiefs of the jarana dancers, and even the linens adorning altars—both at church and in people’s homes—transform communities into landscapes of embroidered flowers. During religious celebrations, even the statues of the Virgin Mary and the crosses are dressed in colorful embroidered garments.

For those curious about Yucatán’s rich cultural tapestry—particularly its religious embroidery—these festivals offer a visual feast. Embark on an annual journey through these celebrations to experience the artistry firsthand: from the embroidered costumes of the vaquerías to the guild banners parading through processions and mass.

A Calendar of Festivities in Yucatán

![2501 Gremios Merida by Yucatan Today]() January 6: The Feast of the Three Kings is celebrated in Tizimín.

January 6: The Feast of the Three Kings is celebrated in Tizimín.- February 2: Valladolid hosts a grand festival honoring the Virgin of Candelaria.

- March: Though lacking major saint celebrations, this month marks the arrival of spring.

- April 28: Chumayel honors Santo Cristo de la Transfiguración.

- May: As the month of the Virgin Mary, May sees widespread celebrations, especially on May 3, the feast of the Holy Cross—a symbol sacred to the Maya people. In Xocen, the revered Pueblo Sagrado de la Cruz Maya (sacred town of the Maya cross), pilgrims arrive from across the eastern regions and Quintana Roo.

- June 13: San Antonio de Padua is celebrated in Chemax, Tekit, and Tunkás, while on June 24, the towns of Cuncunul and Abalá pay tribute to San Juan Bautista, the patron saint of embroiderers.

- July 14: Santo Domingo is honored, and in Halachó, celebrations for Santiago Apóstol include dances, processions, and pilgrimages.

- August 15: The Virgin of the Assumption is feted in many towns, with grand celebrations in Temozón, Tetiz, and Xocen.

- September 14 and 16: San Román is celebrated in Dzan and Izamal, and September 29 marks the feast of San Miguel Arcángel in Hoctún and Maní.

- October 18: Izamal honors Cristo de Sitilpech.

- November 13: Tekax pays tribute to San Diego de Alcalá.

- December: Festivities abound, with December 8 celebrating the Virgin of the Conception in Izamal, December 12 honoring the Virgin of Guadalupe in Acanceh, and the year concluding with the Nativity feast in Espita.

In collaboration with UNESCO and Banorte, the Yucatán Government is spearheading efforts to revitalize the region’s cherished Maya embroidery traditions. Through the creation of a State Embroiderers’ Council, a safeguarding plan has been set in motion to ensure this rich cultural heritage thrives for generations to come. A key initiative of the plan is to strengthen the traditional fiestas patronales, ensuring they remain vibrant celebrations of Yucatán’s living legacy.

These festivals are more than events—they are windows into a world of artistry, devotion, and community spirit that define Yucatán’s heart and soul.

Preserving Heritage Is Everyone's Responsibility

Heritage is the cultural legacy we inherit from the past, experience in the present, and pass on to future generations. Cultural heritage goes beyond monuments and collections of objects. For instance, Yucatecan Maya embroidery is a cultural heritage of Yucatán and has a safeguarding plan that ensures its continuity today and for years to come. This plan outlines hundreds of actions identified by the embroiderers themselves to preserve and protect this tradition.

Often, we think safeguarding heritage is solely the responsibility of the government or specific communities. However, it is truly a responsibility shared by all of society.

The Keepers of Intangible Cultural Heritage

The primary stakeholders are the cultural bearers—members of a community who recognize, reproduce, transmit, transform, create, and embody cultural traditions within and for their community. In this case, the embroiderers, whose life experiences preserve the knowledge, skills, and techniques that make up this cultural heritage.

But Yucatecan embroiderers are not alone. They are supported by various stakeholders of intangible cultural heritage, who, alongside the tradition bearers, include:

- Collectives or groups: Governance bodies and families.

- The Community of belonging

- Local, municipal, and state governments

- Civil society, NGOs, and foundations

- Cultural associations and museums

- Festivals and patron saint celebrations

- Academia: Research institutes, universities, and the education system, which study, document, and transmit knowledge.

- The private sector: Businesses, hotels, and other enterprises that supply, market, and promote cultural heritage.

- International organizations: Such as the UN, UNESCO, UNDP, etc.

- Media and social networks: Channels that communicate and raise awareness about cultural heritage.

Today, the role of the international community is also highlighted. Together with the states party to the convention, they contribute to safeguarding intangible cultural heritage through cooperation and mutual assistance.

Maya Embroidery and Carnaval: Expressions of Identity and Cultural Heritage

Maya embroidery—Cultural Heritage of the State of Yucatán—and Carnaval—a cultural and community expression—represent two vibrant and meaningful cultural manifestations in México and other regions of Mesoamerica. While distinct in nature, both expressions share the role of preserving the identity of the people, transmitting ancestral knowledge, and strengthening social cohesion over time.

Maya Embroidery: A Textile Art with History

Maya Embroidery is a form of artistic and symbolic expression that has been passed down through generations, especially among women. Through traditional techniques and geometric, floral, and zoomorphic patterns, Maya textiles reflect the cosmovision, history, and social status of those who wear them. The state of Yucatán has the largest variety of embroidery stitches in Mexico and has developed distinctive styles, where the hipil and other embroidered garments stand out for their vibrant colors and intricate designs. Beyond its aesthetic value, Maya embroidery is also an economic livelihood for many indigenous communities, allowing them to preserve their traditions in a globalized world. The terno, for example, is worn across all levels of Yucatecan society, from women in rural communities to the governor's wife.

Carnaval: A Festival of Tradition and Cultural Resistance

Carnavales, celebrated in various parts of Mexico and Latin America, are festivals that combine dance, music, masks, and rituals that blend Indigenous, African, and European elements. These festivities, which usually precede Lent, represent a space for freedom, satire, and renewal, where communities express their creativity and cultural reaffirmation. In regions with a strong Indigenous presence, carnivals incorporate pre-Hispanic myths and ancestral symbolism, becoming a reflection of the resistance and evolution of local traditions.

Carnaval in Yucatán: Tradition, Joy, and Cultural Identity

Carnavales in Yucatán are one of the most anticipated festivities of the year, combining music, dance, colorful parades, and traditional elements that reflect the region's rich cultural heritage. These celebrations, of colonial origin, have evolved to incorporate both Indigenous and mestizo influences, becoming a unique expression of identity and popular joy.

Traditional Elements of the Yucatecan Carnival

- "Vaquerías" and the Yucatecan Jarana – In some municipalities, carnaval includes the traditional jarana dance, accompanied by charanga music and regional attire.

- Costumes and satire – As in other carnivals around the world, in Yucatán, people wear costumes and masks to engage in social critique or represent popular characters.

- Festive Gastronomy – During Carnaval, delicious Yucatecan snacks such as panuchos, salbutes, and marquesitas are widely enjoyed.

A Cultural Heritage in Evolution

Both Maya embroidery and carnivals have successfully adapted to social and economic changes, preserving their essence while engaging with new generations. While embroidery stands as a testament to textile wisdom and a connection with nature, carnivals showcase the ability of communities to transform adversity into celebration. Both are examples of Intangible Cultural Heritage that, rather than being relics of the past, remain alive today, strengthening the identity and sense of belonging of the communities that practice them.

The Chichén Itzá Cenote and the Textile Tradition in Yucatán

The Yucatán Peninsula is the youngest part of México. It is a large coral plate that emerged from the sea 12 million years ago, formed mainly of Calcium Carbonate (CaCo3). Because it is so permeable, rainwater does not accumulate on the surface—instead, it filters down and dilutes the CaCo3, forming cavities of different sizes along the way: holes, pans, rejolladas, grottos and cenotes (from the Maya dzonot). Once in the subsoil, the filtered water forms large underground rivers.

These cavities that form a karstic landscape have long impacted Maya spirituality; the underworld, with its caves and cenotes, full of stalactites and stalagmites, is very important in the Maya vision and philosophy. Let us remember that the epic narrated in the Popol Vuh begins when the gods of the underworld challenge the twins Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué. In history, during the Spanish conquest and persecution and the Caste War, caves have been an important refuge for the Maya population.

In the great cenote of Chichén Itzá, a sacred space for the Maya ancestors, hundreds of carbonized textiles were found. Some made of cotton and others of henequen fiber; some hand-woven, others made with a backstrap loom, and still some embroidered with “satin stitch” (chuuy kab in Maya), although researchers who are not from the area do not recognize the presence of this technique.

Six hundred pieces make up the collection of this textile treasure, which is kept at the Palacio Cantón Anthropology Museum in Mérida. This is a significant fact because chuuy kab is still present in the Peninsula and is one of the three most widespread stitches in Yucatán. It is used to create “bouquets” of colored flowers that adorn everyday hipiles and luxury ternos, and it has become part of the pedal and motor machine embroidery under the name “macizo.” So the “grandmother” of the machine “macizos” could be that stitch that is apparently present in several textiles from the Sacred Cenote in Chichén Itzá, taking the origin of embroidery back to pre-colonial roots.

The relationship between the cenotes and the Yucatecan Maya embroidery is a reflection of the deep connection that the Maya have with their natural environment and their cultural heritage. Cenotes have been sources of life, sacred spaces and inspiring elements for the textile art of the region. Through embroidery designs, the memory of the cenotes is kept alive, transmitting from generation to generation the respect and veneration for these bodies of water. Preserving both the cenotes and the art of embroidery is a fundamental task to keep alive the cultural and ecological identity of Yucatán, ensuring that these traditions endure over time and continue to inspire future generations.

Due to its techniques, uses and adaptation to changes, but also due to its importance as a regional identity trait, Yucatecan Mayan embroidery is already listed as part of Yucatán’s intangible cultural heritage; the embroiderers themselves, accompanied by UNESCO, the State Government and the Banorte Foundation, are implementing a safeguard plan that favors its permanence into the future.

The New Traditional Maya Yucatecan Embroidery

Embroidery is an important symbol of Maya Yucatecan identity. It has adorned the traditional gala outfits, the elegant and colorful ternos that brighten and illuminate the vaquería and jarana nights of the state’s patron saint festivals, as well as many other significant official and private events. It has also embellished the everyday dresses of Maya women—the hipiles—since ancient times. Additionally, embroidery has graced the ternos of numerous images of the Virgin Mary, the shrouds of crosses, and both domestic and ritual tablecloths that adorn altars throughout the region. It continues to be a fundamental decorative element in the clothing worn by women throughout their entire life cycle, from birth to death, including baptisms, first communions, weddings, funerals, and mourning ceremonies.

Changes in lifestyle have not put an end to the use of embroidery; instead, embroidery itself has adapted to the new demands of today’s Maya women and men. And now, they share it with the world.

There are embroideries adapted to meet the demand for modern urban and rural clothing, as well as other types of products.

Contemporary clothing with Maya embroidery

Perhaps the most notable embroidered garments, as they remain closest to tradition, are the hipil-blouses. These are essentially hipiles adapted into blouse form, widely embraced by women, young girls, and children from both rural and urban areas due to their beauty and deep cultural significance. Additionally, guayaberas or filipinas—men’s traditional shirts—are now commonly worn with embroidery. Maya embroidery has also been applied to more Western-style clothing and various accessories, including table linens, jewelry, textile art, backpacks, and handbags, among many other items.

Although these are now modern products, they remain distinguished by their unique designs. Their patterns feature the signature Yucatecan flowers, geometric motifs, arches, and other elements that give them their distinct identity.

Hand embroidery vs. digital and sublimated embroidery

However, the outlook is not entirely positive, considering the rapid growth of digital embroidery and sublimation printing, which pose a threat to the very existence of traditional hand embroidery.

UNESCO Mexico, together with the Government of Yucatan, the Banorte Foundation and the State Council of Embroiderers, has developed a safeguarding plan that includes short, medium, and long term actions to ensure that Maya embroidery remains viable and is strengthened to improve the standard of living of the bearers and achieve shared prosperity.

We all share the responsibility of safeguarding intangible cultural heritage. To this end, UNESCO, the state government, and Fundación Banorte have launched an integral project to preserve Yucatecan Maya embroidery, recognized as a cultural heritage of the state of Yucatán. This initiative involves all the aforementioned stakeholders, placing the embroiderers at the heart of the effort.

Photography by UNESCO, Carlos Guzmán, Alicia Navarrete, H. Ayuntamiento de Mérida, Violeta Cantarell and Olivia Camarena and Yucatán Today, for its use in Yucatán Today.

UNESCO and Maya embroidery. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 436, in Abril 2024.

A Brief History of Yucatecan Maya Embroidery. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 437, in May 2024.

Hand Embroidery in Yucatán. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 438, in June 2024.

Artisan Machine Embroidery in Yucatán. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 439, in July 2024.

Embroidery and Life Cycle in the Yucatán Maya. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 440, in August 2024.

Ceremonial and Ritual Embroidery in the Maya Communities of Yucatán. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 441, in September 2024.

Embroidery and Janal Pixan. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 442, in October 2024.

Magical Villages and Maya Yucatec Embroidery. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 443, in November 2024.

Regional Embroidery and Identity in Yucatán. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 444, in December 2024.

Embroidery in the Patron Saint Festivities of Yucatan. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 445, in January 2025.

Embroidery in the Patron Saint Festivities of Yucatan. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 446, in February 2025.

Maya Embroidery and Carnaval: Expressions of Identity and Cultural Heritage. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 447, in March 2025.

The Chichén Itzá Cenote and the Textile Tradition in Yucatán. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 448, in April 2025.

The New Traditional Maya Yucatecan Embroidery. First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 449, in May 2025.

Author: UNESCO

UNESCO is the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. It seeks to build peace through international cooperation in Education, the Sciences and Culture (From History of UNESCO, 2024).

In love with Yucatán? Get the best of Yucatán Today delivered to your inbox.

Related articles

The hipil: What it is, how to wear it, and how to buy it

Learn the history and meaning of the Yucatecan hipil. Combine it, take care of it and always look elegant and authentic with the perfect hipil.

Let's Talk About Handcrafts: Embroidered Garments and Panama Hats

Thinking of taking an embroidered garment or some panama hats? Stick around for a couple of recommendations.

January 6:

January 6: