The Chicxulub Crater

Of all the places in Yucatán with a Maya name,

the one that became world-famous is among the hardest to pronounce:

Chicxulub (cheek-shoo-LOOB).

Humans discovered the existence of dinosaurs in the 19th century. Over time, more fossils were found and identified, and today, at least 300 genera and 700 distinct species of dinosaurs have been recorded. For decades, scientists and enthusiasts alike wondered what could have caused so many animals to completely vanish from the face of the Earth.

How did the dinosaurs go extinct?

Various hypotheses, such as volcanic eruptions and climate change, were long considered as possible explanations for the extinction of the dinosaurs. Perhaps the most important clue at hand was the discovery of a geological clay layer, about 65 million years old, enriched with iridium—a rare element on Earth but abundant in meteorites. This led to the hypothesis that the impact of a massive asteroid had injected enormous amounts of pulverized rock into the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and ultimately causing the extinction of the dinosaurs.

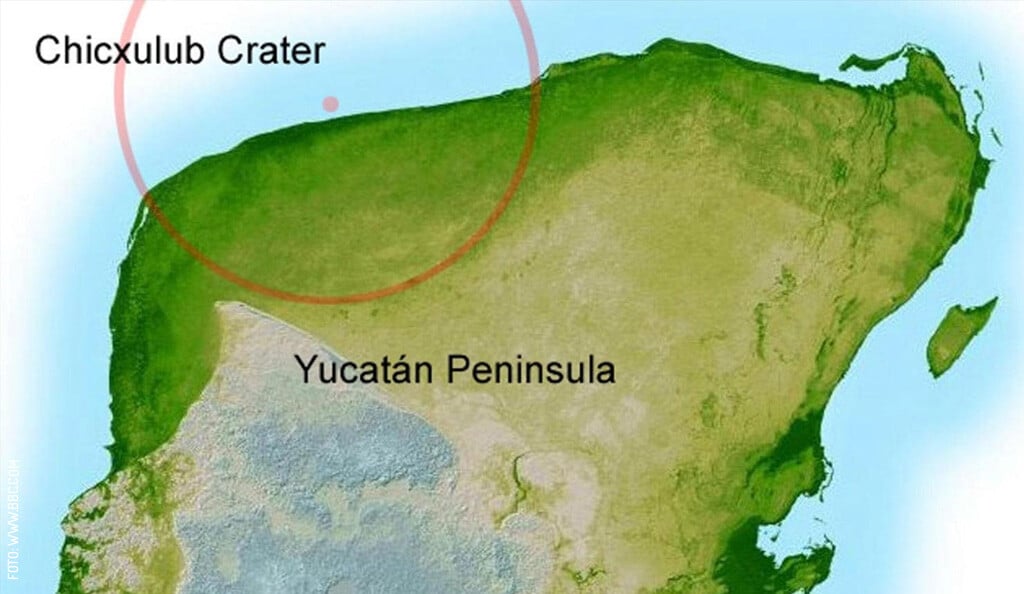

However, an impact with such catastrophic consequences would have left some visible traces. Scientists searched for a crater roughly 200 kilometers (120 mi) in diameter. Across the Earth's surface, only three craters of that size existed, yet none matched the estimated age indicated by the iridium layer.

It wasn't until the 1980s that the answer was discovered—hidden at the feet of Yucatecos for as long as humanity had existed.

How was the Chicxulub crater discovered?

One of the consequences of oil exploration is the geophysical study of the ground. In 1981, reports emerged of magnetic and gravitational anomalies in an area approximately 200 kilometers across, located within the Gulf of México. Additionally, traces of andesite—a type of rock formed when lava cools and solidifies—were found in this same area. If, like some researchers at the time, you're paying attention, you probably already know where this story is going.

Between 1991 and 1994, further studies confirmed the origin of the iridium layer that encircles the Earth. The discovery revealed that this layer, found about a kilometer (300 ft) below the present-day surface, originated from an asteroid impact—which struck roughly where the beautiful port of Chicxulub, Yucatán, stands today.

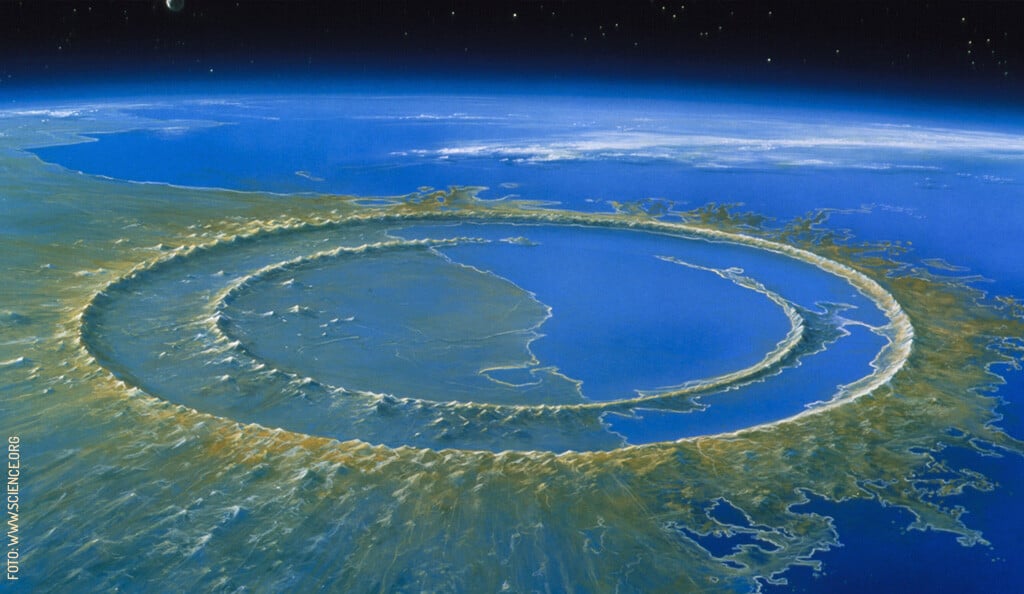

The moment of impact in Chicxulub

It is estimated that the asteroid in question, measuring between 10 and 15 kilometers (6 to 9 miles) long (roughly the size of Mount Everest), crashed into Earth at a speed of around 18,000 kilometers per hour (11,200 mph). In what is now Yucatán, the impact was instantaneous and devastating, releasing kinetic energy equivalent to nearly 5 billion atomic bombs like the one detonated in Hiroshima in 1945. The temperature soared to 5,000ºC (9,000ºF), turning the Earth’s surface into liquid, while the gypsum on the seafloor vaporized instantly. Winds reached speeds of up to 1,000 km/h (620 mph) (a hurricane is considered Category 5 when winds reach 250 km/h or 155 mph), and mega-tsunamis surged with waves between 100 and 1,500 meters (328 to 4,900 feet) high.

Across the rest of the world, the effects were not immediate, but they were catastrophic. Tons of rock and minerals, both solid and vaporized, were suspended in the atmosphere. This blocked sunlight, disrupting photosynthesis and altering global temperatures—two factors that wreaked havoc on the food chain. After this hellish event, the Earth was plunged into a worldwide impact winter that lasted at least five years. It is estimated that the Chicxulub meteor impact led to the extinction of 76% of all species that existed on Earth at the time.

The Chicxulub crater, 66 million years later

However, the Chicxulub meteor did not wipe out all life on Earth. Larger species (including non-avian dinosaurs), which had greater food requirements, were the most affected. Meanwhile, smaller and more adaptable species managed to survive, evolve, and eventually give rise to the biodiversity we are part of today.

Meanwhile, in Yucatán, where the rock that didn’t vaporize turned to liquid, the Earth still bears the scars of the impact. The first is a subtle, 200-kilometer-wide depression. Though the layer of Earth that took the impact is now buried a kilometer underground (with much of it beneath the Gulf of México), the compacted rock has left behind a circular topographical depression, which can be seen in satellite images.

The second scar is the incredible cenotes and caves found throughout Yucatán. The fracturing of rock and variations in soil density allowed rainwater to seep in more easily. Over hundreds of millennia, the limestone dissolved, creating hollow spaces that today are filled with crystal-clear turquoise freshwater. The edge of the crater is known as the "Ring of Cenotes", precisely because this is where rock fractures are concentrated, and where the largest number of cenotes can be found.

In turn, the existence of cenotes was essential for human life in the Yucatán Península—without these natural freshwater reservoirs, settling in this region (which has no rivers or lakes) would have been nearly impossible.

How to visit the Chicxulub crater

As you read earlier, if you're in Yucatán, there’s a good chance you’re already standing inside the crater. The Chicxulub Crater itself isn’t visible, but we can see its consequences—its impact, so to speak—reflected in the limestone, the cenotes, and even in everything the Maya civilization left behind.

However, that doesn’t mean we don’t widely recognize Chicxulub’s place in history. In the main square of Chicxulub Puerto, you’ll find a commemorative plaque—a humble but heartfelt tribute, and the first monument installed in the region after the Chicxulub impact theory gained recognition. There is also the Chicxulub Crater Science Museum, located inside the Yucatán Science and Technology Park, which opens its doors every Saturday, offering guided tours and self-guided visits (it's a good idea to book in advance via their Facebook page).

Additionally, you can visit the Meteorite Museum in Progreso and the Jurassic Trail in Chicxulub Puerto, two interactive experiences that will delight science enthusiasts of all ages.

And, of course, there are the cenotes. Out of the thousands scattered across Yucatán, each one is a living museum, where millions of years are etched into the whimsical rock formations. Don’t miss the chance to visit at least one cenote during your stay. If you need help picking one, check out our cenote guide here.

Want to learn more about the Chicxulub Crater and the extinction of the dinosaurs? National Geographic has a couple of fascinating articles on how volcanic activity in India helped counteract the global winter caused by the Chicxulub meteor impact, and how some dinosaurs survived this mass extinction and evolved into the birds we know today.

First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 448, in April 2025.

References:

- Kornei, Katherine (2018). Life rebounded just years after the dinosaur-killing asteroid struck. Recuperado en marzo de 2025, de www.doi.org

- Lowery, Chris; Hennings, Juli; & Lynch, Harry (2019). EarthDates: Surviving the Asteroid. Recuperado en marzo de 2025, de www.earthdate.org

- www.astrobiology.com

- Urrutia-Fucugauchi, Jaime; Camargo-Zanoguera, Antonio; Pérez-Cruz, Ligia; & Pérez-Cruz, Guillermo. (2011). The Chicxulub multi-ring impact crater, Yucatan carbonate platform, Gulf of Mexico. Geofísica internacional, 50(1), 99-127. Recuperado en marzo de 2025, de www.scielo.org.mx.

- Torres Cruz, Isaac (2025). Cráter de Chicxulub. Extinción de los dinosaurios, en unos cuantos días: Jaime Urrutia. Ciencia UNAM. Recuperado en marzo de 2025, de www.ciencia.unam.mx

- Winemiller, Terance L. (2007). The Chicxulub meteor impact and ancient locational decisions on the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico: The application of remote sensing, GIS, and GPS in settlement pattern Studies (PDF). Recuperado en marzo de 2025, de www.asprs.org

Author: Yucatán Today

Yucatán Today, the traveler's companion, has been covering Yucatán’s destinations, culture, gastronomy, and things to do for 38 years. Available in English and Spanish, it’s been featured in countless travel guides due to the quality of its content.

In love with Yucatan? Get the best of Yucatan Today in your email.

Don't miss our best articles and the monthly digital edition before anyone else.

Related articles

Meteorites and Dinosaurs: Yucatán’s Extraordinary Prehistoric Past

When you think of Yucatán as a land of history, most people think of pyramids and haciendas. However, thousands of millennia before the first humans...

Cenotes, Underwater Sinkholes in Yucatán

[gallery type="thumbnails" ids="68483,99637"] The natural wonders of the state of Yucatán are innumerable and some of the most important and unusual...