The Origin of Our Table: The Maya Milpa

When we talk about México and the foundation of its food system, the milpa is a term you'll hear often. Long before the great pre-Hispanic civilizations arose, the milpa was the heart of agriculture for the peoples of Mesoamerica. As described by Diego Prieto Hernández and Carlos San Juan Victoria in La Nación Maya, the milpa is a specific form of relationship between humans, the land, and the beings of nature. But what exactly is the milpa?

What is the milpa: The Mesoamerican triad

The milpa is an agricultural system based on combining different crops in the same space (polyculture). While specific details varied by region across Mesoamerica, its foundation always consisted of three essential elements: corn (maize), beans, and squash or pumpkin.

What is Mesoamerica?

Mesoamerica is the geographical area where great pre-Columbian cultures developed, spanning the southern half of México, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. Although the civilizations are diverse, they share cultural similarities that distinguish them from other American peoples, such as the Incas, the Sioux, or the Apache.

Other crops were added to this "Mesoamerican triad," including tomato, various types of chili, and leafy greens and herbs. These variations depended on the region’s specific geography, including climate, soil type, and available water sources.

The milpa system and the coexistence of its crops resulted in multiple benefits. First, because the plants grow in complementary ways (corn vertically, beans climbing the corn stalks, and squash covering the soil), the system maximizes the use of the entire cultivable area. Second, since the species are mutually beneficial, the result was more fertile land and crops more resistant to disease and weather. Third, and perhaps most important, the bounty of the milpa formed the basis of a diet exceptionally rich in protein, vitamins, fiber, antioxidants, and all essential amino acids.

Let's meet its key components.

The key components of the Maya milpa

Corn (maíz): The axis of civilization

Rich in fiber, B vitamins, and calcium, thanks to nixtamalization.

Without a doubt, corn remains the principal product of the Maya milpa to this day. While many of us are only familiar with white, yellow, or blue corn, Yucatán has dozens of varieties, differing in size, color, and harvest time.

A curious fact about corn is that it is a completely domesticated grain: Mesoamerican cultures couldn't survive without it, and corn couldn't survive without them. The plant from which corn originated, teocintle, is a wild grass with hard, difficult-to-eat kernels. The oldest evidence of corn domestication in México dates back about 10,000 years.

Corn was of paramount importance to the Maya; unlike other civilizations, the Maya had a corn god. In the creation myth, the grain plays a fundamental role, as it's believed that the father of the twin gods, Hunahpú and Ixbalanqué, returned to earth in the form of a corn plant. Similarly, according to the Maya worldview, humans were created from corn:

“Of yellow corn and white corn was their flesh made; of corn dough were the arms and legs of man made. Only corn dough went into the flesh of our fathers.”

About 3,500 years ago, Mesoamerican civilizations discovered that by cooking corn in alkaline water (limewater, for instance), the grain became easier and tastier to eat. But that's not all: this process, called nixtamalization, also releases Vitamin B3 and several essential amino acids, transforming corn from a nutritious grain into a true superfood.

Squash (calabaza): An edible wrapper

The pulp provides fiber, vitamins, and antioxidants; the seeds (pepita) are rich in protein, fiber, healthy fats, vitamins, and minerals.

Next is squash. In pre-Hispanic Yucatán, three species of squash were cultivated out of the five known across the continent. This, combined with the wide variety of these three species found in the Yucatecan plains, suggests the region may have been the cradle of squash domestication in Mesoamerica.

Theories of squash domestication also suggest that the primary value came from its seeds, which we know today as pepita (pumpkin seeds), rather than the pulp itself. The seeds were durable, nutritious, and delicious. The squashes, then, were originally a simple edible wrapper that eventually won our hearts.

The squash species cultivated in Yucatán (and still grown today) include:

- Cucurbita lundelliana. Known as the “wild squash,” it is the closest to the domesticated species. It is especially abundant in the southern area of the Sierrita de Ticul or Puuc region.

- Cucurbita moschata. This is the domesticated species most closely related to the wild squash; its best-known variety in México is the so-called calabaza de Castilla.

- Cucurbita pepo. This is the most diverse and widely cultivated species in the world today, with varieties that include zucchini (also called Italian squash) and what is known as Yucatecan squash.

- Cucurbita argyrosperma. A close relative of C. pepo, it’s known in Maya as xka’ or xcaita.

Beans (frijol): Protein and flavor

Rich in protein, fiber, iron, minerals, vitamins, and complex carbohydrates.

Four varieties of beans were consumed in Yucatán before the arrival of the Spanish, all belonging to the Phaseolus genus (including lima beans, locally called ibes). Curiously, espelón (the star bean of mukbilpollo or pib) was introduced, as were lentils.

The bean most associated with Yucatecan cuisine is definitely the black bean (frijol negro). It's served k’abax (whole grain, cooked with epazote and salt), colado (strained, blended, and thickened with oil or lard into a creamy soup), or refrito (reduced to a thick paste). However, the white ibes (lima beans), although less visible in the most well-known dishes of Yucatecan cuisine, are a key ingredient in stews like puchero or tóoksel. Tóoksel combines ibes with ground pepita and is cooked over hot stones; served in polcanes (masa balls), you get the Mesoamerican triad in a single bite.

Complementary crops and ancient diversity

Texts written by the Spanish 500 years ago describe at least 36 varieties of vegetables that accompanied the triad in the ancient Maya milpas. These included chilies (maax, green chili, and xcatik), tubers (makal, sweet potatoes, jicama, and yuca), and greens (chaya, cabbage, and tomato), in addition to the gourds and jícaras used as utensils.

The mobile milpa and Maya worldview

A very special feature of the milpa is that the concept of polyculture (growing diverse species together) is believed to have been inspired by nature itself. According to the Maya worldview, the land did not belong to humans but to the gods and other supernatural beings. This gave rise to “mobile” milpas, meaning that crops were planted in different locations depending on climate conditions and soil fertility, often changing locations seasonally. There were also smaller plots cultivated in the solares (house yards). This practice reduced the risk of losing an entire harvest to a natural phenomenon, while also promoting greater variety among species that had to adapt to different conditions of selection, care, and, to some extent, climate.

Fertility and sustainability: The slash-and-burn system

The milpa was based on the slash-and-burn system (roza, tumba, y quema), also called nomadic or itinerant agriculture. This system involved intensive use of a plot of land followed by a long rest period (barbecho or fallow), usually several years long.

Once the land's useful period for cultivation ended, plants and trees were felled (roza y tumba), left to dry, and then burned. While this practice sounds terribly unsustainable today, it was the only viable form of agriculture during Maya times. This is because the high humidity and temperature of Yucatecan soil prevent nutrients from fixing themselves in the ground; they are absorbed by the dense vegetation. This makes it impossible to work a plot repeatedly without fertilization.

It’s true that burning the vegetation where the nutrients reside causes some loss; however, the remainder stays in the ashes to be reabsorbed by the soil, which fully recovers during the fallow period. The burning process also eliminates pests and diseases, giving the land a fresh start.

Currently, many farmers and milperos in Yucatán continue to use this system. The advantages include crops that are free of agrochemicals, both fertilizers and pesticides. However, due to less available land, the fallow periods are often shortened. This creates ecological pressure, as a system that was sustainable for millennia now contributes to global environmental pollution.

The Maya milpa today

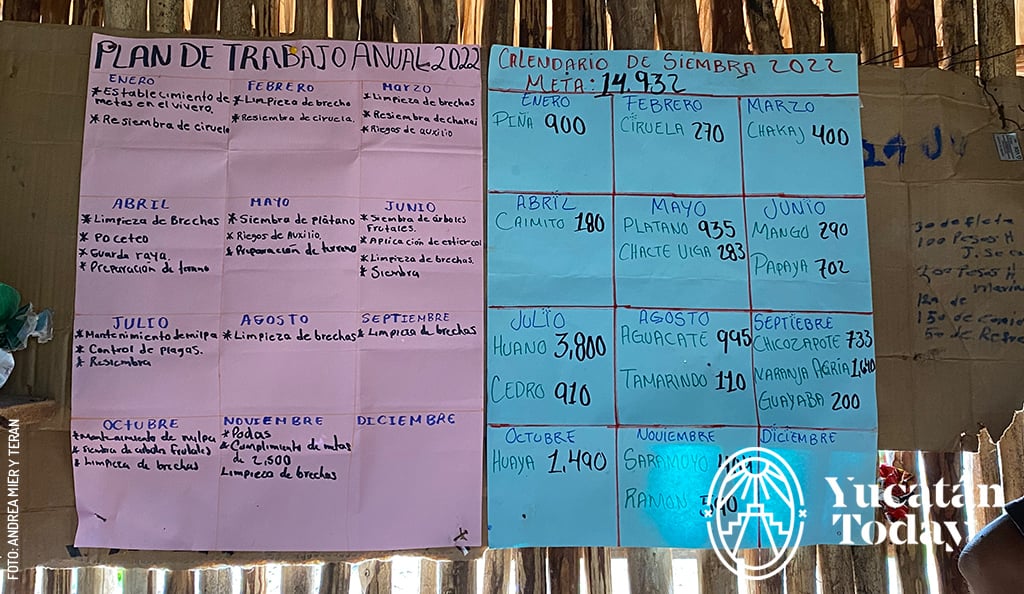

The milpa system continues today, with farmers and milperos working the land, planting the previously mentioned ancestral species along with many others, such as watermelon, melon, cucumber, papaya, plantains, onions, scallions, lentils, espelón, huano, and sago, to name a few.

Photography by Andrea Mier y Terán, Carlos Guzmán and Co'ox Mayab for use in Yucatán Today.

First published in Yucatán Today print and digital magazine no. 455, in November 2025.

Sources:

- Galindo Leal, Carlos & Oliveros Galindo, Oswaldo & Mastretta Yanes, Alicia & Lozada Aranda, Mahelet & Esteva de la Barrera, Daniela & Burgeff, Caroline & Acevedo Gasman, Francisca & Narváez Parra, Aslam. (2020). Calabazas de México [ Cartel ]. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO). Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de bioteca.biodiversidad.gob.mx

- Gamero-Gamero AM, Delgadillo-Martínez J, Cortés-Flores JI, Velasco-Velasco J, Velasco-Cruz C (2020). Propiedades del suelo afectadas por el tiempo de descanso en un sistema de roza-tumba-quema. Ecosistemas y Recursos Agropecuarios 7(1): e2098. DOI: 10.19136/era.a7n1.2098. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.scielo.org.mx

- Graber, Cynthia & Twilley, Nicola. (Host). (2025, July 22). Gastropod: The Colorful Take of México’s A-maize-ing Grain. [Audio podcast episode]. Vox Media Podcast Network, in partnership with Eater. gastropod.com/the-colorful-tale-of-mexicos-a-maize-ing-grain

- Morales Martínez, Mayra Lisset. (2021). Leyendas indígenas. Mayas “Los hombres de maíz”. Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas, Gobierno de México. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.gob.mx/inpi

- Recinos, Adrián. (2005). La creación de los hombres según el Popol Vuh. Arqueología Mexicana. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de arqueologiamexicana.mx

- Rosales González, Margarita & Cervera Arce, Gabriela. (2020). Nuestras semillas, nuestras milpas, nuestros pueblos: Guardianes de las Semillas del sur de Yucatán. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.secihti.mx

- Sánchez de Bustamante, Lucía. (n.d.). Tiempo Mesoamericano. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.inah.gob.mx

- SEMARNAT. (2003). Vegetación y uso de suelo. Informe de la Situación del Medio Ambiente en México 2002. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de paot.org.mx

- Terán, Silvia. (2024). Sustentabilidad milenaria de la milpa maya peninsular. La Nación Maya: Gestación, devenir y resistencia. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

- Terán, Silvia & Rasmussen, Christian & May Cauich, Olivio. (1998). Las plantas de la milpa entre los mayas (Etnobotánica de las plantas cultivadas por campesinos mayas en las milpas del noroeste de Yucatán, México). Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.mayas.uady.mx

- Terán, Silvia & Rasmussen, Christian. (2009). La milpa de los mayas: La agricultura de los mayas prehispánicos y actuales en el noroeste de Yucatán. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.cephcis.unam.mx

- Vela, Enrique. (2010). Las especies de calabaza de México. Arqueología Mexicana. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de arqueologiamexicana.mx

- Venegas-Martínez, Fernanda & Topete-Rojas, Diana & Hernandez Valencia, Grecia Loreley & Almanza-Ruiz, Carla & Chávez-Gaytán, Candy & Padilla-Vega, Luis & Ozuna, César. (2024). La dieta de la milpa como una alternativa sustentable para prevenir la desnutrición en el estado de Guanajuato, México. JÓVENES EN LA CIENCIA. 28. 10.15174/jc.2024.4280. Recuperado en octubre de 2025 de www.researchgate.net

- Prieto Hernández, Diego & San Juan Victoria, Carlos (2024). El camino de la civilización maya. La Nación Maya: Gestación, devenir y resistencia. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH).

Author: Alicia Navarrete Alonso

As a kid I heard that there's more to see than can ever be seen and more to do than can ever be done, so I set out to try. I'm passionate about knowledge and I love to share whatever my own is.

In love with Yucatán? Get the best of Yucatán Today in your email.

Don't miss our best articles and the monthly digital edition before anyone else.

Related articles

The Unknown Side of Yucatecan Cuisine

Tóoksel, Joroch and bean candy are words—and dishes—that I have learned about during my expeditions around Yucatán. Some, like the Tóoksel, I had the...

Queso de Bola, a Matter of Love

Today in Yucatán you can try a marquesita with queso de bola and Nutella, dulce de cajeta, and strawberries in any park.