The Myth of the Maya Calendar

The doomsday clock. The burden of time. The Maya calendar predicts the end of the world. These are the commercialized renditions of an advanced ancient culture that mapped the exact solar cycle of Venus and Mars, forecasted seasonal shifts or droughts, and much more. Popular belief suggests the Maya calendar consists of a circular stone monolith lined with glyphs and a man hunched over carrying more glyphs at its center. Yet there are no known links between the misrepresented international symbol and Maya archaeological monuments or artifacts recovered during expeditions, despite its recognizable glyphs and “The bearer of time” in the middle.

The doomsday clock. The burden of time. The Maya calendar predicts the end of the world. These are the commercialized renditions of an advanced ancient culture that mapped the exact solar cycle of Venus and Mars, forecasted seasonal shifts or droughts, and much more. Popular belief suggests the Maya calendar consists of a circular stone monolith lined with glyphs and a man hunched over carrying more glyphs at its center. Yet there are no known links between the misrepresented international symbol and Maya archaeological monuments or artifacts recovered during expeditions, despite its recognizable glyphs and “The bearer of time” in the middle.

Calculating time for infinity

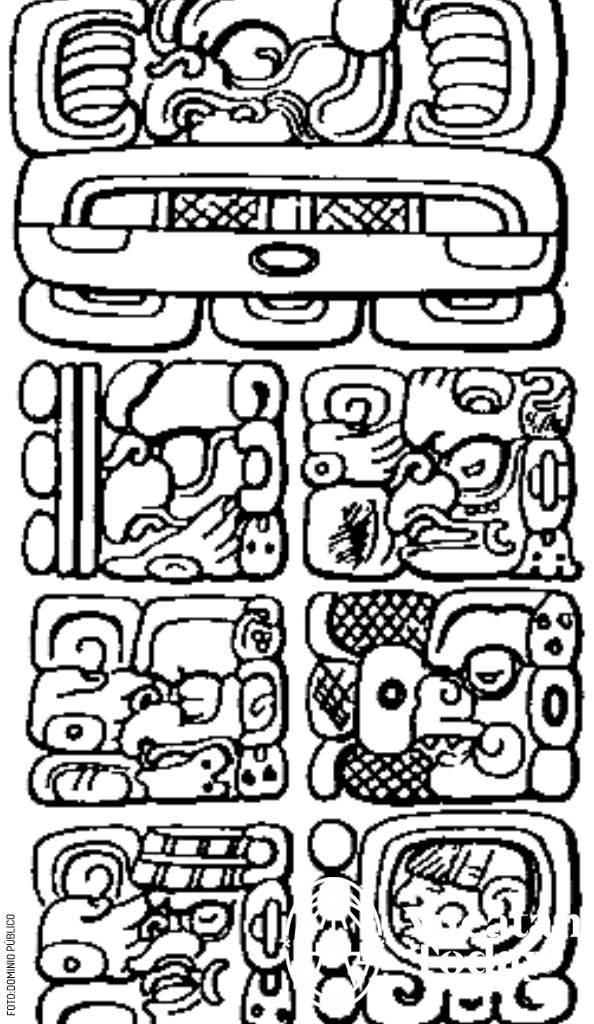

That is not to say the Maya calendar or its symbols are not real. Far from it. There are actually several versions with varied functions this marvelous Mesoamerican civilization used to plan ahead. The Maya used precise mathematical equations to calculate the movement of stars and predict events in the future by using different combinations of intricate interlocking calendar systems.

They centered on a divine calendar, known as “Tzolk’in,” which runs a ritual cycle of 260 days, but there are more familiar ones like “Haab.” This calendar has 365 days but is split into 18 months (20 days per month) with five days spare, the equivalent of leap years. The common consensus among experts suggests their primary function was to forecast agricultural cycles, but meteorological events, spiritual ceremonies, and even taxes or tribute also required their use.

The Maya perception of space and time is as complex as the greatest Chinese and Hindu philosophies conjured in the ancient world, if not even more so. Yet, even though the Maya ventured into mathematics at a cosmic level to reflect upon infinite time and space, they mostly used their advanced technology to improve their daily lives.

“What mattered most was the measurement of the stars and of natural cycles in order to improve man's own life,” historian and academic writer Dr. Mercedes de la Garza said in an interview some years ago for the National Autonomous University of México (UNAM). “This would be for the benefit of agriculture and all daily activities. Apart from having their own 365-day calendar, the Maya had others that meshed together to form not only the periods of one year but also five years, twenty years, four hundred years, and 400 million years, that is, to infinity.”

Dr. Garza said the Maya understanding of the cycles in nature, such as seasonal change, connected with the cyclical concept of time, which worked in harmon y with one another. They thought, just as the sun and stars rotated in circular patterns, that all matter in space and time worked the same way.

y with one another. They thought, just as the sun and stars rotated in circular patterns, that all matter in space and time worked the same way.

“In the Maya culture, time represents the movement of space, that is, there is a very peculiar space-time conception, as the Hindus had, as the Chinese and other great cultures had, which is what determines life,” she said. “So I think that they strove to know the rhythm of the stars, particularly the sun, which was fundamental to all temporality for the Maya. However, they strove to know all that by the belief that both natural and human events were repeated.”

Artistic license

Although the popular image of the bearer of time may have elements of the Maya calendars, it is not the real thing, and there are no sources to track its origin. Some have attributed it to the style of Jean Charlot (1898–1979), a French/American painter, illustrator, and muralist who spent many years working and studying in México. Much of his art depicts human load carriers in different contexts, and there are theories his designs were used later to create the popular image. Charlot was fascinated by the ancient Americas from an early age and worked as an archaeological illustrator at the site of Chichén Itzá, where he published a set of lithographs of Mexican scenes. A large number of his creations featured women, children of Indigenous descent, and, in particular, laborers.

It is unlikely Charlot willingly created a myth for financial gain, considering his known adoration for all things Maya and his efforts to capture unique images at countless archaeological sites. There are others who attribute ‘The bearer of time’ to a marketing gimmick created by Belizean artisans in collaboration with the country’s tourism board. Either way, there are plenty of other original artifacts, monoliths, or calendars that remain colorful and could better represent the Maya civilization in the eyes of the world.

Author: Mark Viales

Independent international journalist from the Rock of Gibraltar. A singer-songwriter with a passion for travel, and a command of four languages.

Receive the latest articles and much more from the best of Yucatán in your email!

Related articles

A Brief Introduction to Maya Culture

Explore the Maya civilization's rich history, divided into three key periods from their early development to the Spanish arrival.

Maya Gods

One of the most devastating consequences of so many Maya codices and sacred art having been burned during the Conquest is that to this day there is...